A grim fairytale - Poe’s “sleeper” hit

|

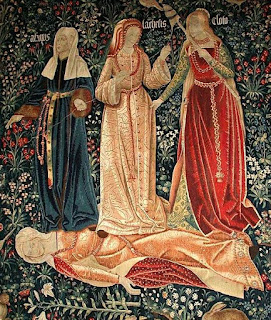

| “Lo! where lies/(Her casement open to the skies)/Irene, with her Destinies!” “The Triumph of Death, or the Three Fates” (ca. 1510-1520) |

Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Sleeper” (1841), is sort of the horror take on the legend of Sleeping Beauty. Claimed to be derived from such wide-ranging works as Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606), Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Cristabel” (1800), William Rufus’ “Oh Lady Love, Awake!” (1826), and John Wilson’s “Edderline’s Dream” (1829), the poem blends Poe’s own interest in the death of a beautiful woman with folkloric and mythological elements that Poe appropriates and even appears to have some fun with in this dark humor-laced, macabre nocturne.

[4Listen to an audio of me reciting the poem at the bottom of this post]

The poem has three distinct movements, starting with opening verses that have been appropriately called a ‘Song of the Moon.’ If ever a poem had an “establishing shot” (in cinema, the first view of a scene, which explains its setting), then the “The Sleeper” ‘s intro feels like a long panning shot, that widens from a close-up of the moon, and slowly tracks down to the “quiet mountaintop” and then finally to the awaiting “universal valley” below it.

The action is set at “midnight” (the middle of the night) in “the month of June” (the middle of the year), a setting reminiscent of the beginning of Dante’s Divine Comedy (“Midway upon the journey of our life ...”). And, just as Dante’s wood was an allegory, Poe’s “universal valley” is a mindscape, a halfway place between life and death. The word “universal” in the phrase “universal valley” means “cosmic” or even “transcendental.” The next few lines, describing flowers and ruins and lakes, sets us up in a typical Poe netherworld. The language is very similar, for example, to the geography of his “Dream-Land” (1844):

Lakes that endlessly

outspread

Their lone

waters—lone and dead,—

Their still

waters—still and chilly

With the snows

of the lolling lily.

The ‘Song of the Moon’ culminates with the introduction of the poem’s heroine: “and lo! where lies/(Her casement open to the skies)/Irene, with her Destinies.” The line acknowledges the earlier version of the poem, simply called “Irenë” (1831), which, thanks to the Poe Society of Baltimore, we have the ‘bootleg’ text for (Phantasmagoria fans will appreciate this: the earlier text is the only extant poem by Poe to explicitly use the word “vampyre”). The line is also a cultural nod to Eirene, the ancient Greek goddess of peace—a fitting reference for a sleeping heroine. There’s also a buried reference to the Sleeping Beauty myth, because the Destinies referenced (usually called the Fates), are an element of the legend, in which the sleeper’s spell is cast by seers who, like the Three Fates of Graeco-Roman mythology, use spindles to weave destinies. (See Amelia Starling’s great exposition on the topic.)

The second movement in the poem is the large, central section, in which the narrator addresses “The Sleeper”, commenting on her beauty, even in death, and seeming to question whether she is really dead or just a stranger, “come o’er far-off seas,/ A wonder to these garden trees.” Many of the lines appear to be written in a mocking tone, reflecting gallows humor: “Strange is thy pallor! strange thy dress!/ Strange, above all, thy length of tress.” This last line could be interpreted as a reference to live burial, as victims of this terrible fate were later found to have longer hair or fingernails than they had when they were buried. We know that Poe was interested in the subject so he would have known this.

At other times, Poe parallels lines included in his own poems. Compare the line in “The Sleeper:” “Oh, lady dear, hast thou no fear?,” to the similar line in “Lenore” (1849): “And, Guy De Vere, hast thou no tear?” The structure and metric signature of the line’s opening phrase, “Oh, lady dear,” is a recurring refrain echoed in the later variants: “Oh, lady bright,” “The lady sleeps” and “My love, she sleeps”—each being four syllables (in poetic terms, two feet) and anchoring the poem thematically while setting its metric pace. Poe mirrors—and, perhaps, also parodies—the other works mentioned above that “The Sleeper” draws from. It is not likely that Poe’s questions to the Lady, such as what is she doing here?, what is she dreaming here?, is she really from here?, etc., are being asked in earnest because of what we find out at the end of the poem (the narrator knows well the answers). These are rhetorical questions asked sarcastically and tongue-in-cheekly. It is delicious black humor.

The final stretch of the poem, beginning “Far in the forest, dim and old,/ For her may some tall vault unfold,” marks a macabre turn in the poem, a flashback to “The Sleeper”‘s childhood, when she played around a secluded family mausoleum, throwing stones at its gates, not realizing that the echoes she thought she heard were in fact the “groans” of the dead. In this part of the poem, the narrator reveals that contrary to the questions posed in the elegiac apostrophe that precedes it, he in fact knew the Lady: he calls her “my love” as he turns the refrain “the lady sleeps” to “my love, she sleeps.” He seems to wish for her a final acceptance of death, perhaps by being transferred from this netherworld where she sleeps in a “casement to open to the sky” to that imposing crypt from her childhood, a final rest.

Poe himself considered “The Sleeper” his best poem. In a letter five years after its final version was published, he wrote, “In the higher qualities of poetry, it is better than ‘The Raven’ — but there is not one man in a million who could be brought to agree with me in this opinion.” Nearly 175 later, that assessment persists, but “The Sleeper” refuses to retreat to her final resting place, continuing to captivate readers with her “strange” and tragic beauty—'A wonder to our garden trees.’

Comments

Post a Comment