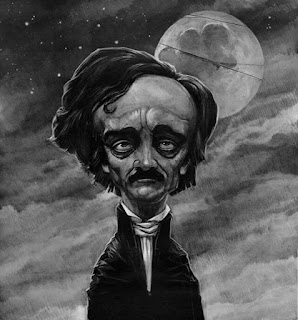

The Poe Outro

In pop music, an “outro” is the concluding segment of a song—the word is made up from the opposite term, an intro , which is the introductory portion: it can be a guitar riff, a distinctive drumbeat, or a combination of similar elements. The introduction to Beethoven’s Fifth (or Symphony No. 5 in C minor) has been called “the most famous four notes in music history” and you can probably hear the ‘ ta-ta-ta-tum ’ in your head as you read this. (It said “ saxo-mo-phone ,” to Homer Simpson.) In the world of pop music, the Beatles were prone to writing memorable outros in songs like “Hey Jude” (‘Na, na, na-na, na-na,’ etc.), “Drive My Car” (‘Beep-beep ‘n beep-beep, yeah’) and “Ticket to Ride” (‘My baby don’t care’). All of these outros switched gears from the verse-chorus-verse-chorus pattern that preceded them into a repetitive loop that was intended to fade out as the song ended. That same idea—a repetitive pattern that takes us out of the pattern set up in the main body—w...