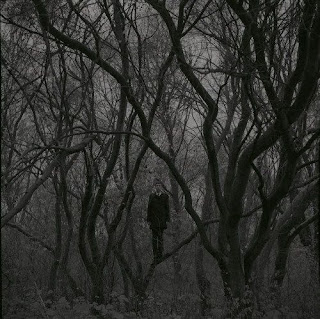

Poe as The Tramp

Charlie Chaplin and Virginia Cherrill in City Lights (1931) If you ever doubted that “less is more,” consider this very short poem by Edgar Allan Poe: I heed not that my earthly lot Hath little of Earth in it, That years of love have been forgot In the hatred of a minute: I mourn not that the desolate Are happier, sweet, than I, But that you sorrow for my fate Who am a passer-by. Originally titled “Alone” when it was first penned in 1827, it was subsequently called “To M—,” and sometimes simply “To —” in later publications. Little is known about this poem, penned when Poe was 19, including the identity of Poe’s Muse or the back-story of their relationship. The poem is, to my mind, an elegant and concise example of Poe’s mastery of meter and poetic devices; in the words of editor Thomas Ollive Mabbott, “ worthy of the term ‘perfect’ .” The lines are alternatingly eight and six syllables long. The rhym...